After thinking about it for more than a week, I finally want to address the issue of why I write the poems I write, and why I write the blog the way I do. Ten days ago, I couldn’t say how the blog relates to the poems, but I’ve really considered it, and now I think I know. But that doesn’t matter anyway--whether I actually know or not; the questions are always more important than the answers.

When I was six or seven, I knew I wanted to be a writer and tried to make sense of my world by writing. Back then, though, and for much of my life, I hid behind abstracts, naming my feelings but never telling the stories behind them. To tell those stories, my secrets, would be dangerous. It could get me into trouble.

I was only a child. I couldn’t risk it.

As a young adult, I survived the telling of my secrets and was willing to write the stories. I tried, but the poems were full of explication, overly sentimental. I didn’t have the tools I needed to do it properly. I had an instinctive appreciation for the music of poetry, and for image and metaphor, but I had no real grasp of how to use them. I didn’t understand that poems are events. I was entering middle-age when I learned, with three kids, a busted marriage, and 32 years of stories to get out.

Once, while I was in grad school, I lamented to Ellen Bryant Voigt, “Who cares about what I write? It seems all I ever write about is my dead sister, my divorce, and my childhood,” to which she replied, “You have to write the poems you have to write first—before you can write the poems you want to write.” I think she meant a sort of clearing out of the obsessions that compel us to write. For me, however, there’s always the next poem I must write, and so the poems like

"My Ass Says Hello," the fluffy, funny things I enjoy and don’t get mired up in, are few and far between.

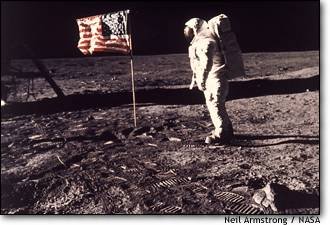

I carry around Gregory Orr’s Poetry as Survival, a book that explains and validates why I write poetry and how I feel better when I do. In chapter one, Orr quotes Isak Dinesen, author of Out of Africa: “Any sorrow can be borne if it can be made into a story, or if a story can be told about it.” I love this quote. It reminds me that I have souvenirs from any tragedy I endure, testaments to my perseverance and survival.

In chapter seven, Orr says, “Story is both primal, a concrete way of ordering experience, and also a way of opening the self to disorder… One of story’s primary purposes is to lay claim to experience. Autobiographical storytelling can take personal experience back from silence, shame, fear, or oblivion. It says, ‘I cherish this,’ or ‘This haunts me.’ It asserts the significance of events in one’s life: ‘This happened to me.’ ‘I did this.’ This is part of who I am.’ ‘This should not or will not disappear, and I act to preserve it by turning it to words and shaping it to story.’"

I’ve personally experienced the power of storytelling, and I teach it every day. I teach it to designers, photographers, art directors, and illustrators, as well as to other writers. Whether you’re telling your story through a visual or a written grammar, your work will be more powerful if it comes from your experience and is told in your unique voice. The photographers in Hank’s Creative Concepts class learned that in 24 hours. I saw their work transcend the expected results that come when you look for a story outside yourself (stained glass, religious icons) to become exquisite manifestations of their own experiences, beliefs and values.

I’ve never felt the need to apologize for my poetry, perhaps because poems are such “made things” that in my mind they might as well be paintings or sculptures. I know that some people, loved ones at that, have been upset or disturbed by my work, but once I commit a story to poetry, I give it its life. If I can get it published, I do. If it ends up in a book, that’s its destiny. There is only one poem in Karaoke Funeral that gives me the slightest twinge of regret, and that’s the title poem, because it exploits the funeral of my children’s great grandmother, a wise, beautiful, woman.

There was no other way to tell the story, though, of how it felt when my touchstones to the past had disappeared, when I no longer had my sister (my only sibling) to poke with, “Hey, remember that time at Aunt Jo’s…" or my husband to reminisce about “the time Sadie ate the Vaseline…" when I had only myself and my suspect memory to rely on. It’s a special brand of loneliness and it needed to be written.

Now, I’ve finished a new book, which is more difficult than the first, because it begins in a place full of hope—a hope achieved through long struggle, a hope that turns out to be short-lived. Everyone ‘goes down’ in this manuscript, not the least of whom is myself. I believe that was true of the first book; I didn’t make myself (the speaker of the poems) smell like a rose in that one either.

But what has this got to do with your blog, Tania? Well, the blog has been a way to exercise, sort of like paddling along in class I and II until I can hit whitewater again. Since I finished the last manuscript in January, I haven’t been able to write poems. I’m not worried. I know they’ll come. I’m just tired is all, worn out from living the life that became that book, and from writing it.

Yet, every day, I see poems--in my house, at school, in the street. I grab those moments and put them down here. Sometimes, as with the poetry, the past gets mixed up with the present. Something reminds me—dontdatehimgirl.com, for instance, and off I go. I feel like telling the story. Because I tell it better now, since I’m not emotionally involved, since I’m able to look back in wonder that such things actually happened—and that the girl I was, the young woman, was so gullible, so stupid, or so hopeful. She was such a survivor.

I took the comments of my ex sister-in-law to heart: “…it is time to move on and let go.” I considered how it must make her feel to read the stories about her brother (whom I did not name or identify in any way) and whether I was indeed stuck, somehow, to still be writing about him.

I thought about my husband and mother, who’ve expressed some hurt of their own about my posts, and who’ve come around as they’ve trusted me to paint a bigger picture of our lives.

I asked myself if I had anything to apologize for.

Then I remembered the Dinesen quote, and that the stories, those mementos, are mine.

No one can tell me whether I should put them away in a drawer or hang them from the lamp post.

And I’m not sorry. I’m not.